A decade on, India’s first solar park has many promises left to fulfil

10 years after the project came up, the villagers of Charanka, the project site, are still waiting for clean drinking water, free electricity, and irrigation. Against the promise of 1,000 permanent jobs, only 60 people in the village have been employed as security guards, grass cutters and for washing panels, with no scope for jobs for women, making families who did not have land or sons the worst victims of the solar park.

Beginning in the 1990s, the forest department shifted away from commercial production toward a greater emphasis on joint-forest management, which resulted in a shift toward an array of broad-leaved (but still not palatable) species being planted, especially in lower altitudes. However, Gaddis were largely left out of many joint forest management schemes mainly because of their migratory practice and were consulted in a “token fashion” for compensatory afforestation for hydroelectric projects in high altitudes.

Beginning in the 1990s, the forest department shifted away from commercial production toward a greater emphasis on joint-forest management, which resulted in a shift toward an array of broad-leaved (but still not palatable) species being planted, especially in lower altitudes. However, Gaddis were largely left out of many joint forest management schemes mainly because of their migratory practice and were consulted in a “token fashion” for compensatory afforestation for hydroelectric projects in high altitudes.  The states of Kerala and Telangana have created cooperatives of women farmers which has not only reaped financial benefits but also ensured better social status for the members. The women got familiar with farm practices, government institutes and private agencies, market negotiations and fund management, all of which helped them overcome gender, caste and class barriers

The states of Kerala and Telangana have created cooperatives of women farmers which has not only reaped financial benefits but also ensured better social status for the members. The women got familiar with farm practices, government institutes and private agencies, market negotiations and fund management, all of which helped them overcome gender, caste and class barriers

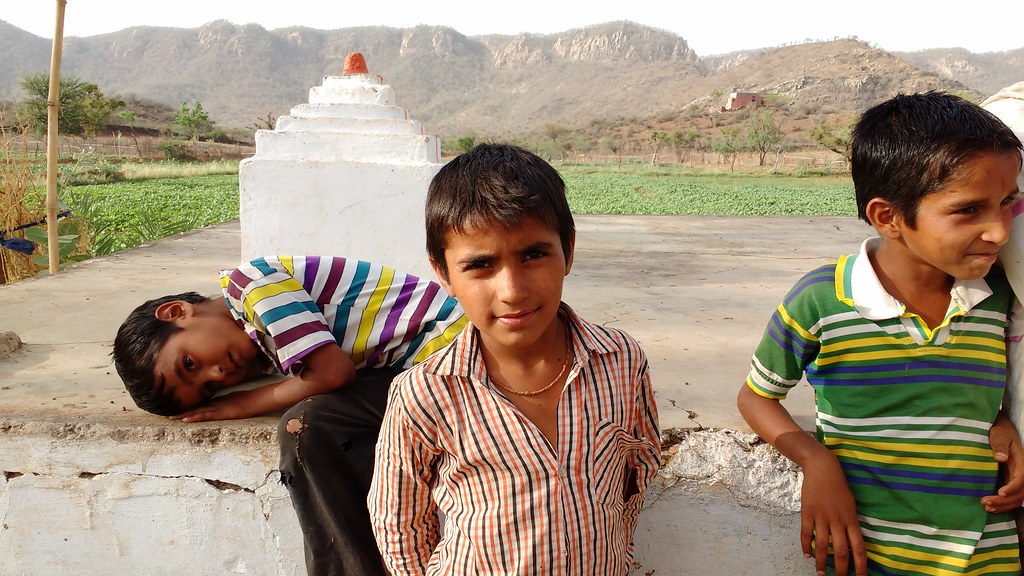

The impact of climate crisis on people across the world is highly disproportionate but no other group is as vulnerable as children in low income families of developing countries. Children are not emotionally and physically capable of understanding the dangers during extreme weather events and are dependent on adults for their survival. They are more susceptible to water and vector borne diseases, malnutrition and they are forced into labour due to economic challenges induced by climate crisis.

The impact of climate crisis on people across the world is highly disproportionate but no other group is as vulnerable as children in low income families of developing countries. Children are not emotionally and physically capable of understanding the dangers during extreme weather events and are dependent on adults for their survival. They are more susceptible to water and vector borne diseases, malnutrition and they are forced into labour due to economic challenges induced by climate crisis.

Conversion of common lands for solar parks, industrial zones and plantations have undermined the productivity of pastoralists. Even though many nomadic pastoralists have taken to settled livestock rearing, they continue to face challenges in accessing local village grazing lands. Settled living also leads to young men migrating to cities to seek alternate jobs or to pursue higher education leaving women with additional responsibilities, including grazing, lopping and finding new sources of fodder and water.

Conversion of common lands for solar parks, industrial zones and plantations have undermined the productivity of pastoralists. Even though many nomadic pastoralists have taken to settled livestock rearing, they continue to face challenges in accessing local village grazing lands. Settled living also leads to young men migrating to cities to seek alternate jobs or to pursue higher education leaving women with additional responsibilities, including grazing, lopping and finding new sources of fodder and water. There are 56 percent households in rural India which do not own any farm. On the other hand, around 7.18 percent households own more than 46.71 percent of total agricultural land thus signifying that few people continue to hold on to large resources. Land reforms failed in their main task of empowering the poor who continue to suffer due to current market-led reforms. Average availability of common land, which is best bet for landless for fodder or farming, has also been declining.

There are 56 percent households in rural India which do not own any farm. On the other hand, around 7.18 percent households own more than 46.71 percent of total agricultural land thus signifying that few people continue to hold on to large resources. Land reforms failed in their main task of empowering the poor who continue to suffer due to current market-led reforms. Average availability of common land, which is best bet for landless for fodder or farming, has also been declining.

The devastating impacts of big hydel projects, including submergence of habitats, alteration of river ecosystem, and displacements, are well known. Alternatively, India has been harnessing hydropower through small, community-based set ups which range from traditional water flour mills of the hills called gharats to the modern projects which generate power between 0-100 kw. These plants, being decentralised and community controlled, offer a viable option to habitations which are off the conventional grid system.

The devastating impacts of big hydel projects, including submergence of habitats, alteration of river ecosystem, and displacements, are well known. Alternatively, India has been harnessing hydropower through small, community-based set ups which range from traditional water flour mills of the hills called gharats to the modern projects which generate power between 0-100 kw. These plants, being decentralised and community controlled, offer a viable option to habitations which are off the conventional grid system.