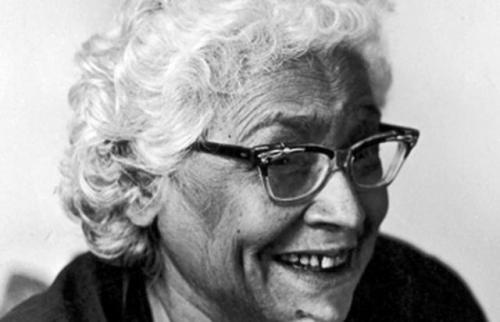

THERE EXISTED once an outspoken woman who went an extra mile to challenge the “second sex” conception of women with breathtaking honesty. She turned out to be a rebellious and provocative writer with her voluminous writings tracing a successful path towards a very ‘uncommon’ approach. She bravely challenged the “other” image or position of women in the society.

“…she dared to raise the veil of hypocrisies in Indian society,” said Qurratulain Hyder, a contemporary of the fearless Urdu writer, Ismat Chughtai. This holds true as her acclaimed and contentious writings provide a clear understanding of the often “misunderstood woman.”

Chughtai’s stories are largely woven around the social milieu of lower middle and middle-class women, which she has keenly observed from close quarters. “An Uncivil Woman”, a book edited by literary historian Rakshanda Jalil tries to capture the essence and volcanic power that was Ismat Chughtai. It works to extensively bring out the tonality and depth of her written work.

Chughtai’s stories are largely woven around the social milieu of lower middle and middle-class women, which she has keenly observed from close quarters

India’s first female Dastangoi, Fouzia Dastango recently brought alive the feminist writing of Ismat Chughtai’s “Nanhi ki Nani” at ‘The World Book Fair’ as she sang it with commendable modulations. This Dastangoi, being a woman, endeavours to break through the boundaries of the female world into the male world. She continues to strive each day to revive the dying art of storytelling, a tradition of 13th century.

This was followed by an enriching panel discussion on Chughtai and “The Uncivil Woman”. Rakshanda Jalil, a literary historian, critic and author, offers an exceptionally intelligible statement in the book that is both rational and eloquent.

Video from an earlier event on writings of Ismat Chugtai

Jalil offers a critical approach to Ismat Chughtai that tries to redefine the lens through which one should approach the writer and her writings. She seems to be shocked and appalled to realise that even after being popular, Chughtai had very few critical studies. She had critics but not much critical work attributed to her.

Jalil offers a critical approach to Ismat Chughtai that tries to redefine the lens through which one should approach the writer and her writings

The most explicit discussion was of the Progressive Writer’s Movement that is also known as ‘Anjuman Tarraqi Pasand Mussanafin-e-Hind’. The progressive literary movement advocated social equality and attacked social injustice. It was characterised by a change in society and literature alike. Ismat Chughtai considered herself a part of it. Ideological writing was considered ‘sehatmand literature’ that portrayed reality. The sexual innuendos (mention of ‘breast’ in the story “Lihaaf”) in Ismat Chughtai’s writings supposedly led to obscenity, creating a stir in society and ‘unnecessary’ attention of public.

Raskshanda Jalil highlighted the similarities and dissimilarities between Ismat Chughtai and her contemporary and friend, Saadat Hasan Manto. Chughtai though did not see herself as a proponent of homosexuality and gay movement but emerged to be so in minds of readers. Jalil contends the fact that “Lihaaf” did not contain any obscenity and it was more so in the minds of the reader, as submitted by Chughtai’s lawyer in a court case that followed the publication in pre-independent India.

Chughtai had a feminist approach but was not essentially a ‘feminist writer’ at core as she focuses on both men and women alike in various writings. She does not only mention Muslim women in her works but women as a whole and was enamoured by Marxism. The discussion also brings forth the fact that Chughtai was not influenced by another progressive Urdu writer Rashid Jahan, but admired her as she once said, “Unhone bigaad diya (She spoilt me).”

She does not only mention Muslim women in her works but women as a whole and was enamoured by Marxism

The forward to the book by Krishan Chandra seems problematic to Jalil, but happens to be her favourite part too as Chandra says: “Ismat Chughtai’s writings are as complicated as women’s hearts.” Rakshanda Jalil feels that this statement is benign patriarchy but also gives an entry into a lucid and ‘correct’ understanding of Chughtai. The discussion also had a discussion of the language, mocking approach and themes of Chughtai and her strong comment on religion in “Nanhi ki Nani” in the lines: “…allah bhi sharma jaye...”

The discussion was an enriching one touching upon various elements. The overshadowed personality of the remarkable writer that Ismat Chughtai is needs to be reversed. Jalil attempts to challenge that conception.

Liked this story? GoI Monitor is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to Support Our Efforts