We have just started getting a handle on malaria but the future is not all cheery

INDIA'S TRYST with malaria is never ending. In 2017, we had 0.84 million cases, down from around two million in 2001.

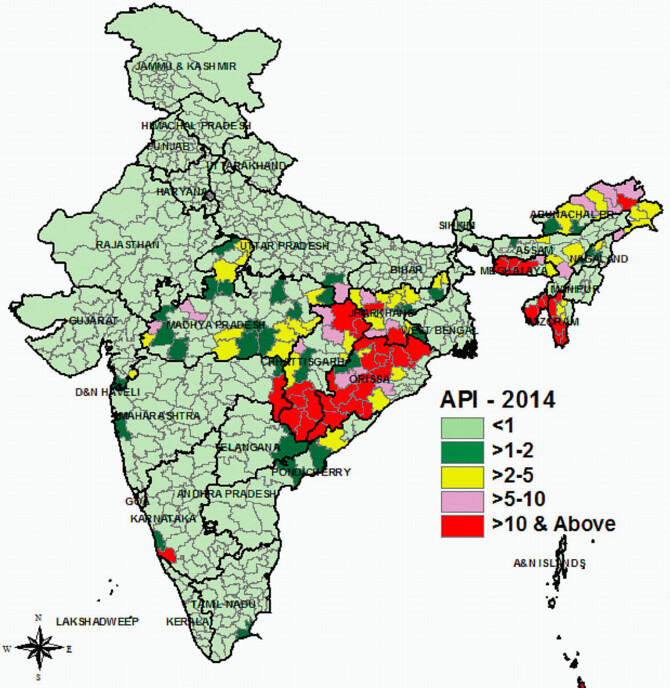

Still, around 80 per cent of India’s nearly 1.3 billion population is at a risk of malaria with most cases originating in hard-to-reach areas of Eastern, Central and North-Eastern India.

While the number of cases has declined by 60 per cent over 2001, there are concerns that malaria is still being under reported. Other issues include the systemic resistance to drugs which were previously used to limit vector growth.

Around 35 countries have been certified to be free of malaria and another 21 on their way to reach their target of zero transmission by the year 2020.

In our neighbourhood, Sri Lanka and Maldives have also achieved the malaria-free status and Bhutan will be there soon. India aims to be a malaria-free nation by 2030 and recent efforts under the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP), have shown steady decline of malarial transmission, at least in numbers.

Malaria, at one time a rural disease has diversified into various ecotypes, including forest malaria, urban malaria, rural malaria, industrial malaria, border malaria and migration malaria. But it’s the geographic conditions, lack of access to treatment and preventive measures besides low awareness in the areas with high prevalence that remain the big challenges.

Artemisinin combination therapies (ACT) and preventive measures like insecticide-treated mosquito nets are being pushed under the programme.

Malaria in India is spread by two parasites, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax, with mosquitoes being their carrier. Over the years, P. falciparum has developed resistance to Chloroquine, a drug used commonly to treat the infection.

In 2017, every single malarial death was attributed to P. falciparum, majority of which were in high-risk States of north-eastern, eastern and central India, said a paper published by Defence Research and Development Establishment (DRDE). P vivax is largely concentrated in big cities and can be controlled by Cholroquine.

But it’s P. falciparum which is spreading far and wide, It is now found in more than 60 per cent of malaria cases whereas in 2001, the cases were equally divided between P. falciparum and P. vivax. An upgraded artemisinin-based combination therapy is now being used to treat P. falciparum. In addition, a programme to detect early warning signals of a malarial threat and deployment of ASHA workers for surveillance and monitoring are already underway.

While number of cases have declined from two million cases in 2001 to close to a million cases in 2017, most of it is recorded after 2010 when the artemisinin-based combination therapy was introduced and insecticide-treated mosquito nets became available.

With climate change opening new frontiers for vector-borne diseases in the hitherto untouched upper Himalayan range, the challenge will further rise in the years to come.

A study by the National Institute of Malaria Research indicate that malaria could spread to new areas of Uttarakhand, Arunachal Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir during the next 20 years.

In the eastern Himalayas, the window of malaria transmission would increase from 7–9 to 10–12 months in length because of the region’s humid and wet weather with mild winters that make it highly conducive for mosquito breeding, survival and transmission.

But India's east coast would have reduced transmission, because of an increase in temperature, and the western regions would see a minimal impact, the analysis showed.

Another study done in 2005 also indicated that the northern states, including Himachal Pradesh, and Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur and Mizoram in the northeast may become malaria prone.

The extent of vulnerability, however, will depend on the socio-economic conditions. Greater awareness and wherewithal to ensure prevention can thus go a long way.